Caterpillar Club - stories of bailing out of Wellington X9876

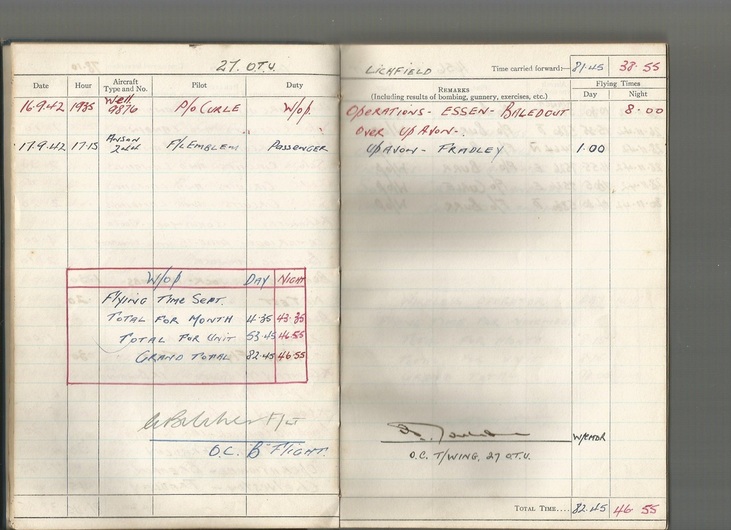

On 16 September 1942, four of the crew of ED559 (Curle, Crapp, Riding and Durdin) had to bale out of their stricken Wellington bomber (number Mk.IC X9876 of 27 OTU). Their target that night was in the Happy Valley - the well-defended city of Essen, home to the famous Krupp steelworks.

After taking off from RAF Lichfield at 1948 hours with four 500lb GP (General Purpose) bombs. They dropped their bombs from 8,000ft at 22:21 hours but were caught in searchlights and their aircraft sustained serious damage from flak over Essen. Flak had destroyed the port aileron, causing Pilot Officer Curle immense handling problems. He initially thought the damage was bad enough to make preparations to bale out over enemy territory.

However, he slowly managed to coax the bomber back to England at the slow speed of just 95 mph. The aircraft was in such a poor state that it would be impossible to make a controlled landing and Curle ordered the crew to bale out at approximately 0315 hours over Wiltshire (the Operational Record Book for 27 OTU notes that they baled out over Andover which is not far from where the aircraft crashed). Harry Riding noted that they baled out near Upavon which is about eight miles due west of where the Wimpy crashed at Collingbourne Ducis in Wiltshire.

After taking off from RAF Lichfield at 1948 hours with four 500lb GP (General Purpose) bombs. They dropped their bombs from 8,000ft at 22:21 hours but were caught in searchlights and their aircraft sustained serious damage from flak over Essen. Flak had destroyed the port aileron, causing Pilot Officer Curle immense handling problems. He initially thought the damage was bad enough to make preparations to bale out over enemy territory.

However, he slowly managed to coax the bomber back to England at the slow speed of just 95 mph. The aircraft was in such a poor state that it would be impossible to make a controlled landing and Curle ordered the crew to bale out at approximately 0315 hours over Wiltshire (the Operational Record Book for 27 OTU notes that they baled out over Andover which is not far from where the aircraft crashed). Harry Riding noted that they baled out near Upavon which is about eight miles due west of where the Wimpy crashed at Collingbourne Ducis in Wiltshire.

The crew that night were:

- Pilot Officer Richard A. Curle RAFVR Pilot 121280

- Flying Officer Errol C. Crapp RAAF Navigator 411113

- Pilot Officer Robert H. Chapman RAAF Bomb Aimer 412481

- Flying Officer Harry Riding RAAF Wireless Op 403699

- Flying Sargeant Garnet W. Durdin RAAF Air Gunner 416149

The fate of Robert Herbert Chapman intrigued me. I initially thought that he may have sustained injuries during the baling out that hospitalised him in Torquay. However, Durdin's account states that all five met up later in the day before flying back to Lichfield.

It actually transpires that Chapman was admitted to the RAF Hospital in Torquay on 20 October 1942 with tonsillitis. Five days later, on the 25th, the hospital was attacked by the Luftwaffe in a tip-and-run mission. The hospital was in fact the requisitioned Park Hotel and was an obvious and large building to target, but had large red crosses on it to denote it as a medical facility.

Chapman was among several fatalities from the attack and was buried at Torquay Cemetery.

It actually transpires that Chapman was admitted to the RAF Hospital in Torquay on 20 October 1942 with tonsillitis. Five days later, on the 25th, the hospital was attacked by the Luftwaffe in a tip-and-run mission. The hospital was in fact the requisitioned Park Hotel and was an obvious and large building to target, but had large red crosses on it to denote it as a medical facility.

Chapman was among several fatalities from the attack and was buried at Torquay Cemetery.

Accounts of baling out by two crew who flew on ED559

There are two accounts from Harry Riding and Garnet Durdin about this incident. Below is Durdin's account, which by coincidence was reported in his local Australian paper on 4 March, 1943, the day ED559 was lost:

Flights Over Germany By Local Airman

A story related in a letter home to his parents of his first flights over Germany by Sgt. G. W. Durdin, Aust. 416149.

"Practically all my time has been occupied fully up until the last few days night flying and of course sleeping a big part of the next day. One night after flying for six hours, I was told to report at 11 o’clock next morning; for what, I did not know. However, when reporting, I was to go on the Dusseldorf raid that night, but the chap whose place I was to take had arrived back at camp, so obviously I was not required, but as you will see, that was just the beginning. The following day our crew was one detailed for the large Bremen raid, after briefing that afternoon, it was postponed-back to bed in anticipation for the following night.

Sure enough, Sunday, 13th, was to be the big day; we were again briefed in the early afternoon in preparation for the late take off. Eleven p.m. had arrived, the large ‘drome was the scene of great activity, when all the engines began to roar. Off into the darkness we left to bomb Bremen, the visibility being that bad we could barely see our own wing tips. It was to be my first operational flight; the same applied to other members of the crew.

It was a queer feeling waiting around all day, but as soon as I occupied my power-operated turret I felt full of confidence. After nearing the Dutch coast, flak could be seen coming up above the thin layer of cloud on our port. It was O.K. for us as the other aircraft was taking the punishment, not ours; that’s just how it was all the way to the target.

Searchlights filled the sky, so at 2 o’clock in the morning we go in to bomb the target, fires burning everywhere. When making the bombing run, one searchlight caught us, then in a fraction of a second they appeared to be all on us. Shells and light flak were exploding all around us, our aircraft being hit occasionally.

It seemed impossible to escape, but after a few minutes the pilot did the trick. “Well done, Dick,” we all said in relief. No sooner said than we caught again. I thought we had it, for my intercom would not work; when the kite was diving at 310 m.p.h. I was just about to jump when I heard voices, so I knew we still had a chance. Next second I nearly went through the top of the turret; by violent evasive action, our pilot Dick had won again. It sure frightened me. The trip home was uneventful in the Wellington, but, believe me, I was pleased to see the English coast; we landed at an American airfield for breakfast. On arriving back at base I was told five of my cobbers having been killed, their plane crashing just after takeoff. But such as it is, it is all in the game, they have all been forgotten about at the camp.

Early the Wednesday morning I had to report again for leave I was anticipating, but I was sadly disappointed, for it was to be another large scale raid. This time the target was one in the Ruhr district of Germany. After checking all the guns and the turrets in general, it was time for briefing. The aerodrome looked the same hive of activity again before the much earlier take off. Our aircraft, a Wellington, was one of the first to be airborne, and it was not long before I was across the coast, testing my guns, which functioned perfectly.

On the way across the Ruhr I saw two night fighters, but fortunately they did not see us, even though they had searchlights. By the time we arrived, the target was well ablaze, and we had no difficulty in finding our spot while we appeared to get through without any trouble. Then we were caught in two searchlights which I soon shot out, for by this time we were flying perhaps lower than we should have been.

Suddenly there was flak whizzing everywhere; we had been badly hit. “Bale out,” Dick said. The navigator rushed up and helped with the controls, they managed to keep it straight, and gain height, all the time thinking we would have to jump. After much trouble we managed to keep clear of the searchlights and flak.

It was impossible to see the ground or sea; we did not know if we were home or not, when we were caught in the searchlights. We gave a signal from the air, and they went out. Naturally we thought we were near the south-east coast of England, but when the wireless operator got our position, we were 100 miles down the French coast. We turned straight for home, getting quite a shock in regards to our position.

One hour later we could see the searchlights of Southampton and the Isle of Wight. Dick said, “I am afraid it will be impossible to land her,” but we still had to get further inland. “You will have to go now, fellows” was the last I heard from pilot Dick. “Rear gunner baling out,” I said, after putting the turret on the beam, and jettisoning the doors, I fell backwards with my parachute on.

The next I knew, I looked up, and saw it was open, knowing I was safe. It’s a funny feeling being suspended in mid-air. I did not know it I was going up or down, until I hit the ground at 3.30 in the morning in pitch darkness, being lucky to miss two high patches of trees, falling in some smaller ones, which helped to take the bump. I wandered around until daylight before looking for a house, where I told my story, but I am afraid they did not believe me, and thought I was a “Jerry”.

So I went a little further to another house where there was a Home Guard major, who had been to Australia. After telling my story he could not do enough for me. I had landed just fifty yards or so from a Home Guard camp, amongst high trees; just as well I did not land on them. I was given an abundance of appropriate refreshments, before getting in touch with a nearby R.A.F. station. A very attractive young W.A.A.F. came out to get me in a transport.

By 6 o’clock that night I had met all my crew members, who also got out unhurt but for a few bruises. Our ship had dived nose first into an open paddock, and burst into flames, and I had lost my only pair of shoes, and my valued first issued dirty cap. What a catastrophe!

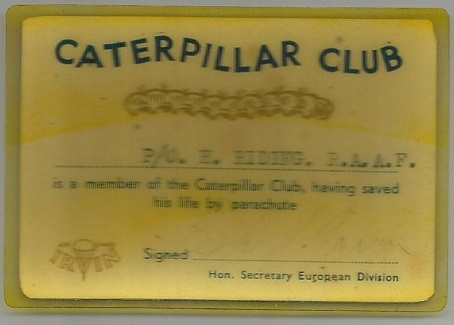

We were all flown back to our original camp, arriving at 7 o’clock that night. I, being the only sergeant, was surrounded in our mess. Consequently it was a very happy landing, for ours was one of the thirty-nine aircraft which were reported missing, you may remember, by your papers. So now I am an official member of the Caterpillar Club.

At present I am spending a week’s leave at Edinburgh, as you can see by the paper I am writing on. Having an excellent time, the Scotch people are very hospitable, different from those further south. Yesterday I saw a large Soccer match in brilliant weather. It made me feel terribly homesick, for I wanted to get back and play for Strath’s against Aldgate, say, at Echunga. If ever I felt that way I did yesterday. What I have seen during the last few weeks makes me think chances are very remote of seeing Australia for a long time. However, I can only hope for the best.

Tuesday I report to an all-Australian Squadron somewhere in England, our crew having to do a month’s training course on the large four engine Halifax aircraft. Flying in these faster and bigger aircraft should help to make the game a little easier.

The weather is just commencing to get cold. This last week is the first time I have been wearing my overcoat since arriving."

* Editor's note. Though Durdin mentions meeting up with all his crew after baling out, I believe that Chapman was seriously wounded. It may have been for propaganda purposes that this was not included.

Flights Over Germany By Local Airman

A story related in a letter home to his parents of his first flights over Germany by Sgt. G. W. Durdin, Aust. 416149.

"Practically all my time has been occupied fully up until the last few days night flying and of course sleeping a big part of the next day. One night after flying for six hours, I was told to report at 11 o’clock next morning; for what, I did not know. However, when reporting, I was to go on the Dusseldorf raid that night, but the chap whose place I was to take had arrived back at camp, so obviously I was not required, but as you will see, that was just the beginning. The following day our crew was one detailed for the large Bremen raid, after briefing that afternoon, it was postponed-back to bed in anticipation for the following night.

Sure enough, Sunday, 13th, was to be the big day; we were again briefed in the early afternoon in preparation for the late take off. Eleven p.m. had arrived, the large ‘drome was the scene of great activity, when all the engines began to roar. Off into the darkness we left to bomb Bremen, the visibility being that bad we could barely see our own wing tips. It was to be my first operational flight; the same applied to other members of the crew.

It was a queer feeling waiting around all day, but as soon as I occupied my power-operated turret I felt full of confidence. After nearing the Dutch coast, flak could be seen coming up above the thin layer of cloud on our port. It was O.K. for us as the other aircraft was taking the punishment, not ours; that’s just how it was all the way to the target.

Searchlights filled the sky, so at 2 o’clock in the morning we go in to bomb the target, fires burning everywhere. When making the bombing run, one searchlight caught us, then in a fraction of a second they appeared to be all on us. Shells and light flak were exploding all around us, our aircraft being hit occasionally.

It seemed impossible to escape, but after a few minutes the pilot did the trick. “Well done, Dick,” we all said in relief. No sooner said than we caught again. I thought we had it, for my intercom would not work; when the kite was diving at 310 m.p.h. I was just about to jump when I heard voices, so I knew we still had a chance. Next second I nearly went through the top of the turret; by violent evasive action, our pilot Dick had won again. It sure frightened me. The trip home was uneventful in the Wellington, but, believe me, I was pleased to see the English coast; we landed at an American airfield for breakfast. On arriving back at base I was told five of my cobbers having been killed, their plane crashing just after takeoff. But such as it is, it is all in the game, they have all been forgotten about at the camp.

Early the Wednesday morning I had to report again for leave I was anticipating, but I was sadly disappointed, for it was to be another large scale raid. This time the target was one in the Ruhr district of Germany. After checking all the guns and the turrets in general, it was time for briefing. The aerodrome looked the same hive of activity again before the much earlier take off. Our aircraft, a Wellington, was one of the first to be airborne, and it was not long before I was across the coast, testing my guns, which functioned perfectly.

On the way across the Ruhr I saw two night fighters, but fortunately they did not see us, even though they had searchlights. By the time we arrived, the target was well ablaze, and we had no difficulty in finding our spot while we appeared to get through without any trouble. Then we were caught in two searchlights which I soon shot out, for by this time we were flying perhaps lower than we should have been.

Suddenly there was flak whizzing everywhere; we had been badly hit. “Bale out,” Dick said. The navigator rushed up and helped with the controls, they managed to keep it straight, and gain height, all the time thinking we would have to jump. After much trouble we managed to keep clear of the searchlights and flak.

It was impossible to see the ground or sea; we did not know if we were home or not, when we were caught in the searchlights. We gave a signal from the air, and they went out. Naturally we thought we were near the south-east coast of England, but when the wireless operator got our position, we were 100 miles down the French coast. We turned straight for home, getting quite a shock in regards to our position.

One hour later we could see the searchlights of Southampton and the Isle of Wight. Dick said, “I am afraid it will be impossible to land her,” but we still had to get further inland. “You will have to go now, fellows” was the last I heard from pilot Dick. “Rear gunner baling out,” I said, after putting the turret on the beam, and jettisoning the doors, I fell backwards with my parachute on.

The next I knew, I looked up, and saw it was open, knowing I was safe. It’s a funny feeling being suspended in mid-air. I did not know it I was going up or down, until I hit the ground at 3.30 in the morning in pitch darkness, being lucky to miss two high patches of trees, falling in some smaller ones, which helped to take the bump. I wandered around until daylight before looking for a house, where I told my story, but I am afraid they did not believe me, and thought I was a “Jerry”.

So I went a little further to another house where there was a Home Guard major, who had been to Australia. After telling my story he could not do enough for me. I had landed just fifty yards or so from a Home Guard camp, amongst high trees; just as well I did not land on them. I was given an abundance of appropriate refreshments, before getting in touch with a nearby R.A.F. station. A very attractive young W.A.A.F. came out to get me in a transport.

By 6 o’clock that night I had met all my crew members, who also got out unhurt but for a few bruises. Our ship had dived nose first into an open paddock, and burst into flames, and I had lost my only pair of shoes, and my valued first issued dirty cap. What a catastrophe!

We were all flown back to our original camp, arriving at 7 o’clock that night. I, being the only sergeant, was surrounded in our mess. Consequently it was a very happy landing, for ours was one of the thirty-nine aircraft which were reported missing, you may remember, by your papers. So now I am an official member of the Caterpillar Club.

At present I am spending a week’s leave at Edinburgh, as you can see by the paper I am writing on. Having an excellent time, the Scotch people are very hospitable, different from those further south. Yesterday I saw a large Soccer match in brilliant weather. It made me feel terribly homesick, for I wanted to get back and play for Strath’s against Aldgate, say, at Echunga. If ever I felt that way I did yesterday. What I have seen during the last few weeks makes me think chances are very remote of seeing Australia for a long time. However, I can only hope for the best.

Tuesday I report to an all-Australian Squadron somewhere in England, our crew having to do a month’s training course on the large four engine Halifax aircraft. Flying in these faster and bigger aircraft should help to make the game a little easier.

The weather is just commencing to get cold. This last week is the first time I have been wearing my overcoat since arriving."

* Editor's note. Though Durdin mentions meeting up with all his crew after baling out, I believe that Chapman was seriously wounded. It may have been for propaganda purposes that this was not included.

Harry Riding's account of baling out

Have paid Jerry a few visits myself lately and you know they are most inhospitable people, somehow or other I think they actually resent us going over there, anyhow they usually put on a very good pyrotechnic show for us, but at times a lot of it comes too damn close for comfort, rather frightening at first, especially when you see it pass through the wings and so forth, also has a vile smell and a hell of a lot of noise to go along with it, those boys toss up everything except the kitchen sink.

Couple of weeks ago we caught a packet that put the A/c almost out of control and we had rather a shaky do getting back to old England, however we made it and then had to hook the old parachute on and jump for it, not a very pleasant sensation, even from 10,000 feet although it gives you a fair amount of time to get the brolly open, landed rather heavily in a Wiltshire wheat field, completely dark too about 3.30 a.m. Wandered round a bit, found a couple of hay stacks that I thought were houses, found they were not, cursed a little, and continued the search which was unsuccessful, so I sat down on some stooks of wheat and awaited the dawn then staggered some 3 miles to a farm house, with a phone and from there everything was O.K. All the rest of the crew landed safely in different parts of the district and we had rather a joyful reunion the same afternoon. Received a few bruises and a shaking up but nothing more serious, still a little stiff and sore, but will get over that I hope.

Couple of weeks ago we caught a packet that put the A/c almost out of control and we had rather a shaky do getting back to old England, however we made it and then had to hook the old parachute on and jump for it, not a very pleasant sensation, even from 10,000 feet although it gives you a fair amount of time to get the brolly open, landed rather heavily in a Wiltshire wheat field, completely dark too about 3.30 a.m. Wandered round a bit, found a couple of hay stacks that I thought were houses, found they were not, cursed a little, and continued the search which was unsuccessful, so I sat down on some stooks of wheat and awaited the dawn then staggered some 3 miles to a farm house, with a phone and from there everything was O.K. All the rest of the crew landed safely in different parts of the district and we had rather a joyful reunion the same afternoon. Received a few bruises and a shaking up but nothing more serious, still a little stiff and sore, but will get over that I hope.