The crew of Lancaster ED559 - Code JA-D

Four of the crew that were to fly on Lancaster bomber ED559 had flown together on several operations whilst with No. 27 Operational Training Unit (27 OTU) at RAF Lichfield in Staffordshire. During the summer and autumn of 1942 Richard Curle (pilot), Errol Crapp (navigator), Harry Riding (wireless operator) and Garnet Durdin (air gunner) flew operations in the twin-engine Wellington bomber. These four men were later transferred to No. 460 Squadron (RAAF) to convert to Halifax bombers before then going onto RAF Lindholme in South Yorkshire in November 1942, home of No. 1656 Heavy Conversion Unit (1656 HCU) to convert to flying the heavies - the four-engine Lancaster bombers.

It was at 1656 HCU that the new crew of seven came together. How the ex-Wellington crew located the three new members - Charles Challoner (bomb aimer), Daniel Gooch (mid-upper gunner) and David Hart (flight engineer) - is unknown. Crews formed themselves and came together by simply asking the required specialist to join them. I have read accounts that the RAF simply put all the various personnel required to make up a crew in a hangar and then let them meet and create a crew socially.

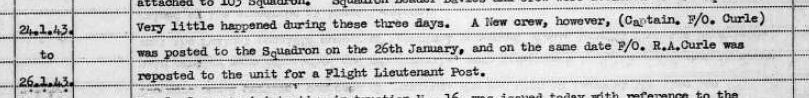

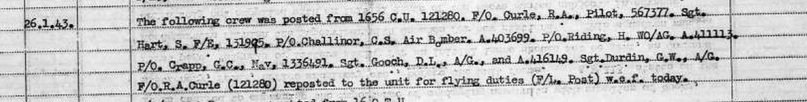

The new crew arrived at RAF Grimsby in Lincolnshire (home to No, 100 Squadron) on 26 January, 1943. On the same day Richard Curle was reposted for a Flight Lieutenant Post (that is Acting F/Lt) as detailed in the below snippet from the 100 Squadron Operational Record Book (ORB).

The new crew arrived at RAF Grimsby in Lincolnshire (home to No, 100 Squadron) on 26 January, 1943. On the same day Richard Curle was reposted for a Flight Lieutenant Post (that is Acting F/Lt) as detailed in the below snippet from the 100 Squadron Operational Record Book (ORB).

The crew then spent the rest of January, all of February and early March training on various Lancaster bombers stationed at RAF Grimsby - this included day and night flying, fighter escort, dummy bomb runs and take-offs and landings.

Crew biographies and photos

Flight Lieutenant RICHARD ALEXANDER CURLESkipper - Pilot

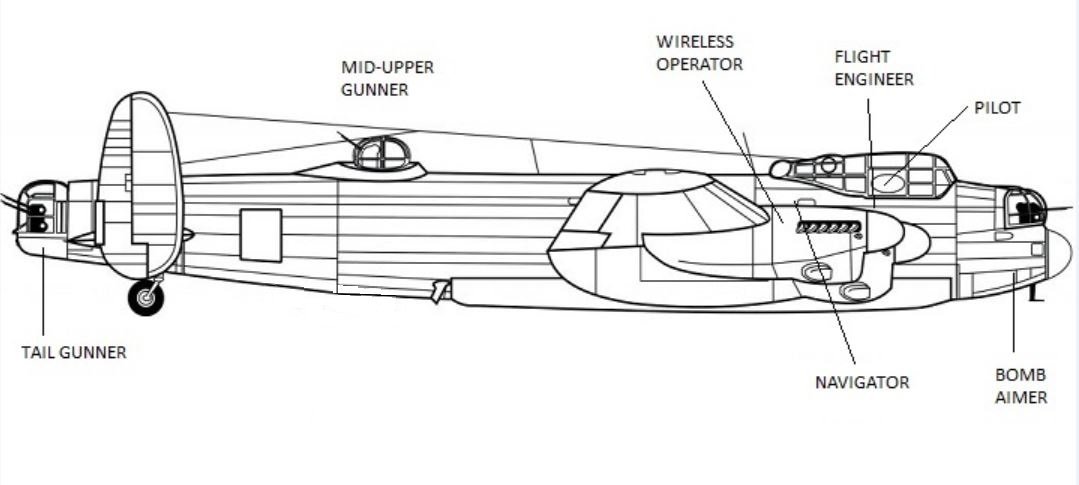

121280 Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) Aged 28 (born 3 September 1914 in Gateshead) See CWGC record | See Records of Service Sat in the armoured seat on the left-hand side of the cockpit, the pilot (known as the skipper) had a clear view of his surroundings through the Lancaster’s canopy. The skipper had the instrument panel with air speed indicator, artificial horizon, turn and bank indicators and rate of climb/descent indicator and a number of other indicators and dials in front of him. As well as the main compass, there was a compass repeater on the wind-shield. The aircraft’s throttle levers and propeller speed controls were accessible by both the pilot and flight engineer. Between his legs was the control column yoke and pedals to control the aircraft and above was an emergency exit hatch in event of a crash landing or water ditching. |

Flying Officer HARRY RIDINGWireless Operator

403699 Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Enlisted 2 March 1941 Aged 25 (born 5th May 1917 in West Maitland, New South Wales) See CWGC record | Australian War Memorial Directly behind the navigator was a small alcove and table for the wireless operator. The W/Op faced forwards towards the radios and there was also a small window to his left (often covered at night) looking out across the leading edge of the port wing. The W/Op would be listening for messages from base. As well as the possibility of the aircraft being recalled he would also pass weather reports, including estimates of wind speed etc, to assist the navigator. |

Sergeant DANIEL LAST GOOCHMid Upper Gunner

1336491 RAF Aged 19 See CWGC record The mid-upper gunner’s turret contained twin .303 inch Browning machine guns and was a tight squeeze. The position offered a 360 degree view (slightly obscured by the tail fins and wings) through which he could traverse his guns. The turret was designed with a fairing so that when tracking and engaging an enemy aircraft the machine guns would not hit the tail or forward astrodome. If required to bale out, the mid-upper gunner had to squirm out of the turret, find and clip on a parachute and exit through the main crew door. If the aircraft had crash landed or made a ditching in the sea there was an escape hatch in the roof of the fuselage. When ditching in the sea, a dingy and other survival gear was stowed in the starboard wing root. |

Flight Sergeant GARNET WALTER DURDINRear Gunner

416149 Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Enlisted 31 March 1941 Aged 25 (born 2 September 1917 in Strathalbyn, South Australia) See CWGC record | Australian War Memorial The eyes and rear defence of the Lancaster was the rear gunner. The rear gunner would enter into the cramped rear turret containing four .303 inch Browning machine guns and not move until the sortie was over. It was often freezing cold (warmth came from a heated suit) and the only communication with the rest of crew would be via the aircraft’s intercom. Always scanning the sky, the rear gunner would alert the skipper to danger and engage enemy aircraft if the Lancaster was not corkscrewing to avoid an enemy attack. The tail gunner’s exposed location was possibly the most dangerous of all the crew positions. Sat in the turret, with armoured doors behind him, if the call came to bale out he would need to retrieve his parachute from behind the doors, clip it on, rotate the turret entirely and exit the aircraft backwards. All this had to be done with the aircraft possibly spinning out of control, praying that the parachute was intact and hoping the turret’s hydraulics still functioned. |

Sergeant DAVID ADRIAN HARTFlight Engineer

567377 RAF Aged 24 See CWGC record Sat to the right of the skipper on a folding seat the flight engineer monitored everything mechanical. He reviewed the status of each off the four engines, set throttle settings, adjusted propeller pitch settings and monitored fuel use. The flight engineer was an extremely busy member of the crew throughout every mission. The flight engineer would, in an emergency, bale out through the emergency hatch in the forward turret. |

Flying Officer ERROL CLIFTON CRAPPNavigator

411113 Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Enlisted 26 April 1941 Aged 24 (born 17 February 1919 in Grenfell, New South Wales) See CWGC record | Australian War Memorial The navigator sat behind the pilot and in front of the wireless operator. Sitting sideways facing port, he used a large table for maps and course charts and above was the astrodome through which rough bearings from the stars could be taken. An instrument panel showing the airspeed, altitude, and other information required for navigation was on the fuselage in front of him. If required he could take measurements of the stars for an astral fix on the aircraft's position. He would also request the crew call out landmarks over occupied territory if they saw them (towns, lakes, rivers, canals etc). He was also responsible for noting down intelligence updates - locations and strength of searchlight and flak batteries. If the crew called out another bomber being shot down he would also note this down with the time. |

Pilot Officer CHARLES STUART CHALLONERBomb Aimer

131995 RAF Aged 37 See CWGC record In the nose of the Lancaster was the Frazer Nash FN5 nose turret with twin .303 inch machine guns. When not manning the machine guns the bomb aimer was responsible for the bomb run. Lying prostrate on the floor viewing the ground through his bomb sight, he communicated with the pilot via the intercom on course corrections. When over the target, the bomb aimer released the bombs (or in the case of ED559's final mission released the sea mines which parachuted into the water). The bomb aimer also provided the navigator with information to aid the aircraft's course. At the front of the bomb aimer’s position was the forward escape hatch, measuring just 22 inches by 26.5 inches, through which he, the pilot and flight engineer would try and exit the aircraft. |